I was talking to Dustin during lunch today when the topic of the circle of fifths came up. He’s studying this week for the “history of music theory” exam, and the Circle, for the purposes of that exam, falls under the category of “pitch spaces” or (according to Wikipedia) “models [that] typically use distance to model the degree of relatedness, with closely related pitches placed near one another, and less closely related pitches placed farther apart. Depending on the complexity of the relationships under consideration, the models may be multidimensional.” The Circle is probably one of the most common and elementary forms of these models, and merely has two dimensions, connecting the twelve pitches of the chromatic scale cyclically to each other by way of perfect fifths: C next to G next to D next to A and so on. (Or the way I was taught: “Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle.”)

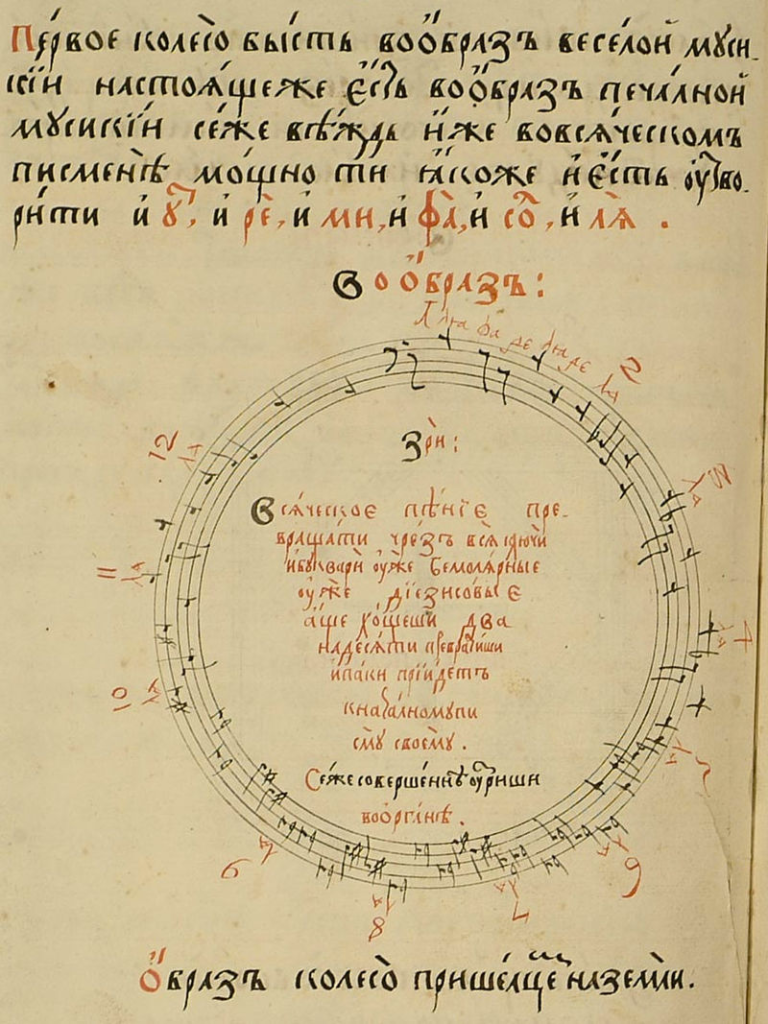

Now, I’m not a music theorist, but one has to live under a rock to not know about one of the most inescapable maṇḍalas of Western music theory, especially given its utility for memorizing key signatures and understanding modulation and functional harmony. So naturally I was curious about when people started drawing this stuff–a curiosity naturally met with long-established responses. Now, the most sensible, historicist thing to do is first to understand early instantiations of the Circle in context: that its appearance in Heinichen’s (1683–1729) treatise on thorough-bass accompaniment continues a long tradition of “envisioning a musical circle” as a result of “the need to play chords or chord progressions at all possible pitch levels,” a tradition Gregory Barnett traces back to the 1590s (“Tonal Organization in Seventeenth-Century Music Theory,” in The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, edited by Thomas Christensen. Cambridge UP, 2002). It is also helpful to loosen the definition of the Circle a little to include diagrams that are essentially the same (for example, key signatures instead of letters), for example the Circle of the Ukrainian composer Nikolay Diletsky (c. 1630–after 1680).

But I am interested in a sillier exercise. The moment I became curious about the history of the Circle I started thinking about Ming- and Qing-dynasty music theorists who made ample use of similar diagrams in their discussions of xuangong 旋宮, or “rotating the do” along an imaginary circle of keys in musical transposition. I am, in other words, involuntarily lead toward a “which first?” way of thought that had already erected famous either-ors such as Zhu Zaiyu 朱載堉 and Simon Sevin, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Issac Newton, Johannes Gutenberg and Bi Sheng 畢昇. Emotions tend to run high when this way of thought is applied to the invention of things and ideas that are deemed highly significant in world history, and fortunately the Circle is not among those ideas. And neither do I think this sort of problems needs to be resolved in the arborescent idiom of originality and filiation. I’m instead much closer to Charles Peirce’s opinion when he writes, in the last of the five Monist papers published between January 1891 to January 1893 titled “Evolutionary Love:” “I believe that all the greatest achievements of mind have been beyond the powers of unaided individuals; and I find, apart from the support this opinion receives from synechistic considerations, and from the purposive character of many great movements, direct reason for so thinking in the sublimity of the ideas and in their occurring simultaneously and independently to a number of individuals of no extraordinary general powers” (The Essential Peirce, vol. 1. Indiana UP, 1992).

Now, just as “folk” intellectual history sometimes attributes the modern Circle to the Pythagorean tuning by the interval of the fifth, it is not hard to suggest that the fundamental seed of the Circle in China can be found in early texts such as the Huainanzi (139 B.C.E.), which connects the “generative” relations between pitches–which is current parlance is simply the perfect fifth interval–to a general ontogenetic theory of everything that begins with the differentiation of the primordium:

黃鍾為宮,宮者,音之君也。故黃鍾位子,其數八十一 [. . .] 下生林鍾。林鍾之數五十四 [. . .] 上生太蔟。太蔟之數七十二 [. . .] 下生南呂。南呂之數四十八 [. . .] 無射之數四十五 [. . .] 上生仲呂。仲呂之數六十 [. . .] 極不生。

The huangzhong (“Yellow Bell” or C) pitch is the tonic, the lord of sounds. Thus huangzhong marks the beginning, measuring to eighty-one [. . .] It generates linzhong (G) by decreasing the number to fifty-four [. . .] which generates taicu (D) by increasing the number to seventy-two [. . .] which generates nanlü (A) by decreasing the number to forty-eight [. . . until] wuyi (A#/Bb), measuring to forty-five, generates zhonglü (F) by increasing the number to sixty [. . .] where the extreme has been reached and thus the generative process comes to an end.

《淮南子 · 天文訓》

The numbers, when considered in proportions, denote the lengths of the pitch-pipes in their relation to the fundamental pitch huangzhong: the length of the linzhong or G pipe would be two-thirds (54:81) of that of huangzhong, and so on. The Huainanzi describes the method of tuning through these precise measurements, but the verb connecting each pitch to the next is taken directly from the ontogenetic cascade of the Daodejing passage quoted earlier in this musical pericope:

道始於一,一而不生,故分而為陰陽,陰陽合和而萬物生。故曰「一生二,二生三,三生萬物。」

The Way begins with Oneness, yet Oneness does not generate. Thus, Oneness is divided into Yin and Yang. Yin and Yang conjoin and harmonize, and from there ten thousand things are generated. Thus [the Daodejing] says: “Oneness generates Two, Two generates Three, and Three generates ten thousand things” (Daodejing, ch. 42).

《淮南子 · 天文訓》

This cosmogenetic vocabulary makes the ontological relationship between its terms–that is, in the first passage, the relation between pitches–ambiguous. Is the connection between C and G something akin to an evolutionary process unfolding over time, or does “generation” establish a relation of filiation between two pre-existing entities? Surely, to spatialize the generative relations between the twelve pitches in the chromatic scale in the form of the Circle, the linear sequence that zigzags up and down (due to the not-at-all abstract requirement that the pitches stay within one octave) needs to be replaced by a different movement, more constant in its mathematicization of the generative relation–a different “musemathematics.” The linearized hierarchy between notes in the chromatic scale needs to partially disintegrate so that the line may close into a circle, a process facilitated by the introduction, into Chinese music history, of a multiplication of musical modes.

All evidence points to a surprisingly late period–the Tang dynasty (618–907 C.E.)–as the period in which the now-canonical phrase geba xiangsheng 隔八相生 (generation by the eighth step) was coined, and retrospectively projected back to an obscure passage in the Book of the Former Han (111 C.E.) as one of the “ancient wisdoms” about music. The Book of the Sui, whose compilation concluded in the year 621 under the supervision of Wei Zheng 魏徵 (580–643), tells the story of the Kucha musician Suzup (fl. 6c.) in the company of Empress Ashina (551–582) of the Celestial Türks when she became the empress to Emperor Wu of Norther Zhou (r. 560–578) in the year 568, who greatly expanded the modal palate of Chinese music through a simple combinatorics:

合成十二,以应十二律。律有七音,音立一调,故成七调十二律,合八十四调,旋转相交,尽皆和合。

[Combining the keys based on huangzhong, taicu, linzhong, nanlü, and guxian with the other seven], a total of twelve keys are created. Each key contains seven tones (i.e. notes in the major pentatonic scale with the addition of “altered-sol” and “altered-do,” each lowered by a semitone from the unaltered counterpart), and each tone can become the tonal center of a mode. Thus there are seven modes and twelve keys, and in combination they become eighty-four modes that spiral and turn, mutually intersect, and are always harmonious with each other.

《隋書 · 音樂中》

Scholars have speculated on the South Asian or even Byzantine origins of Suzup’s modal theory (which he learned from his father, a distinguished musician in the “Western Realms” 西域), but what matters here is how it frees the twelve keys from the linear sequence of their ontogenesis and renders them effectively interchangeable, becoming one of the two coordinates that structure an increasingly complex musical repertoire. While the Book of the Sui documents a general state of confusion following Suzup’s demonstration of the various musical modes (using linzhong G as gong or the tonic, one official objected, is blasphemous and incompatible with elegant music), it appears that this combinatorial modal theory eventually caught on and became the basis of the famous twenty-eight modes of Tang imperial banquet music (燕樂二十八調).

The “spiral and turn” amongst the eighty-four modes in music of this period is little understood today, however, not least because of the conflicting and opaque descriptions of musicologists of later dynasties and the scarcity of notated music from the period itself. But if comments by learned musicians such as Jiang Kui 姜夔 (1155–1209) are to be believed, what we would today call modulation (and which medieval musicians would know as fandiao 犯調) would have been a more common occurrence in Tang music than in music of second millennium C.E., of which sizable corpora in various traditions have survived in notation.

It is in this context that we see the first reformulation of the generative relation between keys a perfect fifths apart as the coherent, consistent movement of geba xiangsheng 隔八相生 (generation by the eighth step), where “eight” denotes a different mathematicization of pitch, no longer the ratio between the lengths of pitch-pipes but distance along the arc of the chromatic circle.

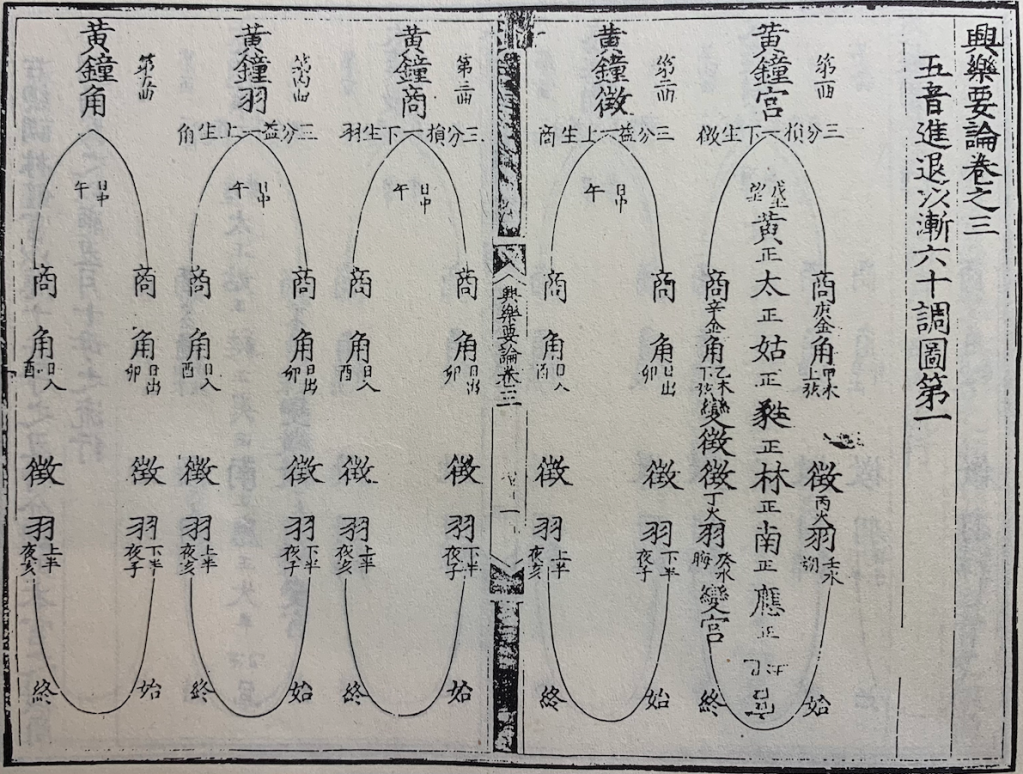

A few decades after the compilation of the Book of the Sui, the final volume in the partially-lost treatise Yueshu yaolu 樂書要錄 commissioned by the Empress Wu Zetian adopts Suzup’s language almost verbatim, explaining in depth the generative relations between the twelve keys and how, with the rotation of gong 宮 or the tonic along the chromatic circle, different pitches come to occupy the seven scale degrees. This phenomenon, which only a century ago was difficult to accept for Suzup’s audience in the Northern Zhou court, is also referred to in the name that has since become standard, xuangong 旋宮 (the rotating do).

旋宮法

黃鐘均: 黃鐘為宮,太簇為商,姑洗為角,蕤賓為變徽,林鐘為徽,南呂為羽,應鐘為變宮。

林鐘均:林鐘為宮,南呂為商,應鐘為角,[大呂]為變徽,太簇為徽,姑洗為羽,蕤賓為變宮。

[. . .]

The method of rotating do

In the key of huangzhong C: huangzhong C is do, taicu D is re, guxian E is mi, ruibin F# is fi, linzhong G is sol, nanlü A is la, yingzhong B is ti.

In the key of linzhong G: linzhong G is do, nanlü A is re, yingzhong B is mi, [dalü C#] is fi, taicu D is sol, guxian E is la, ruibin F# is ti.

[. . .]

《樂書要錄 · 卷七》

It is in the accompanied diagrams to this discussion that we see one of the earliest chromatic circles in Chinese music theory, reproduced above. Each of the twelve trapezoidal shapes on the outer layer of the diagram represents a pitch, with huangzhong or C (the key of the eleventh month) placed in the lower-left. Within each trapezoid, on the top is a circle in which is written the name of the pitch, below it (and connected to the circle with straight lines) are the seven scale degrees or modes, to each is further connected the key in which the pitch appears as that scale degree. Reading the huangzhong trapezoid in this way for example, we can find that huangzhong yu 黃鐘羽, or the C Aeolian mode in modern parlance, is to be found in the key of the second month or jiazhong 夾鐘 D#/Eb. In the center of the diagram are lines connecting pitches a perfect fifths apart–forming a familiar star dodecagon–and on the outside are the seven scale degrees, placed next to their respective pitches in the huangzhong key.

Undoubtedly, Suzup’s combinatorial modal theory, alongside the general influx of music and musicians from Central Asia around the same period, laid some of the most important groundwork for a radially-symmetrical spatialization of the twelve pitches alongside a systematization of how scale degrees “rotate” along this circle through the generative relation between pitches a perfect fifth apart. But this efflorescence of songs and modes was quickly subdued, in the royal science of lülü xue 律呂学 anyway, through the establishment of new correlations between the twelve keys and the twelve months of the calendar. The interval of the perfect fifth, formerly the steps in an ontogenetic process creating the twelve pitches from the differentiation of the primordium, becomes re-interpreted, already in the treatise commissioned by the Empress Wu Zetian, as the rhythmic movement of cosmic pneuma (qi 氣) across months and seasons. In a story told in depth in Lester Hu’s dissertation, we find in early modern musical treatises influenced by Yueshu yaolu 樂書要錄 that each of the twelve months of the calendar becomes associated with a pitch (with huanzhong usually being the eleventh month of the year), and each of the five modes (the altered-sol and altered-do are usually excluded) become associated with further subdivisions of the month (based on lunar phases) as well as various times of the day (based on the position of the sun). The perfect fifth, in other words, takes on yet further cosmogenetic significance in Chinese music theory of the second millennium, as music becomes seasonal and the passage of calendrical time becomes nothing but the progression through the various keys and their modes. The huangzhong C of the eleventh month emblemizes the peak of yang energy, and is succeeded by–through the introduction of counteracting yin energy in the form of a shortened pitch-pipe–linzhong G of the sixth month, with each subsequent movement along the pitch-pipes’ zigzag resulting in a similar leap between keys eight months apart. What in today’s music theory is termed the dominant-tonic relation, which typically only applies to modulations within a single piece of music, is in this lineage of musical thought the fiber of more-than-human time that weaves every piece of music into an interconnected whole through the pulsation of yin and yang.

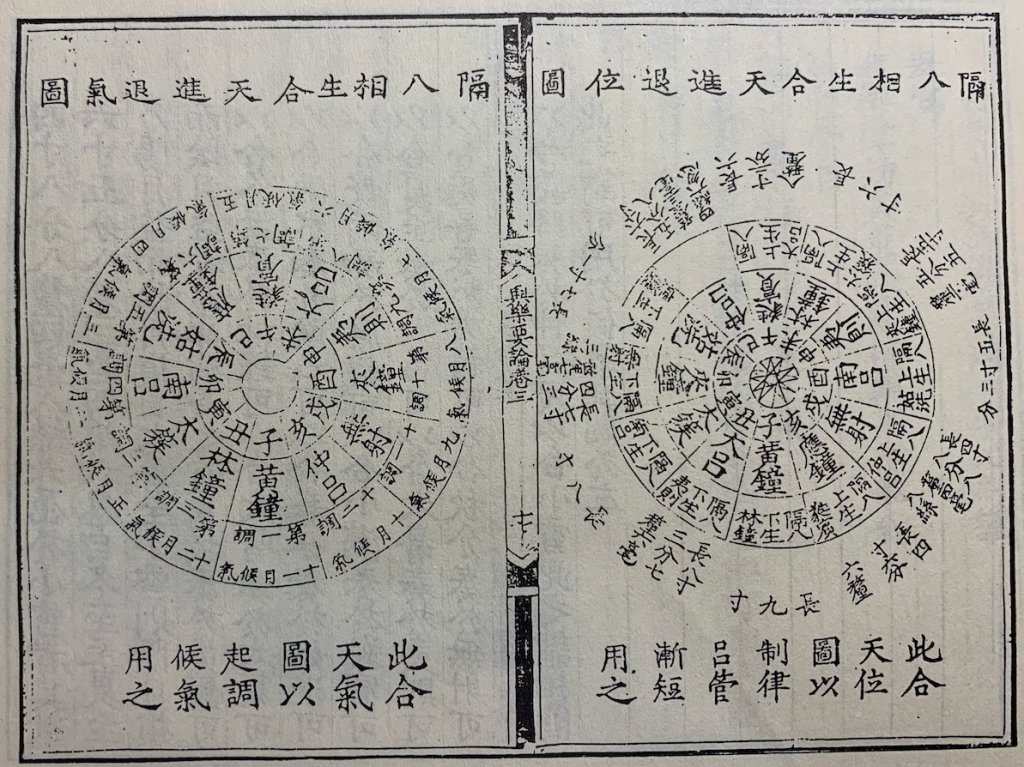

This multiplicity of the relations between pitches–on the one hand a chromatic sequence spanning an octave and on the other a progression encapsulating the movement of cosmic energies–was what prompted the prolific music theorist Li Wencha 李文察 (c. 1493–1563), in a guide to musical appreciation addressed to the Emperor titled Xingyue yaolun 興樂要論, to create what is, to my knowledge, the first circle of fifths in the Chinese tradition. Again, cosmogenetic theory becomes the backbone of music theory, but here the overarching frame is no longer that of Daodejing but the more combinatorial models of the Classic of Changes and, most directly, the five elemental phases that admit different sequential arrangements depending on whether their generative (sheng 生) or destructive (ke 克) relations are to be emphasized. In his own words:

近世但知有宮商角徽羽之序,而不知有宮徽商羽角之序。夫造化既有水火[金木]土,必有木火土金水,然後能變化既成萬物。然則樂調中獨有宮商角徽羽而無宮徽商羽角,其可以盡屈伸流行之妙乎?

People today know the sequence of do-re-mi-sol-la, but not the sequence of do-sol-re-la-mi. Given that the creation and transformation of the cosmos has the phase-sequence water-fire-[metal-wood]-earth (the “destructive” relations), there must also be the phase-sequence wood-fire-earth-metal-water (the “generative relations), and then these phases can transform and eventually become ten thousand things. Yet if in musical modes there is only do-re-mi-sol-la but not do-sol-re-la-mi, how can those pitches fully make use of the wonders of ebbs and flow?

《興樂要論 · 卷三》

The key to understanding the relation between pitches is thus not to prefer one set of relations over others but to consider the interplay between multiple sets of relations, the mutual transformation of calendrical and pneumic time. Returning to the “zigzagging” of pitch-pipes lengths in the tuning system described in early sources, Li Wencha reiterates that it should be understood as the pulsation of yin and yang–atrophy and hypertrophy–with a coherence despite its apparent lack of uniformity, and should therefore be thought of as having a continuity as important as the sequential succession of months characterized by lunar movements. Hence, the need to present two circles side-by-side: the gradual, incremental shortening of pitch-pipes on the right, a diagram of positions (位圖), and the circle of fifths on the left, a diagram of energetic pulsations (氣圖).

And this, I think, is the first circle of fifths in Chinese music theory (the earliest extant one, anyway), and the end of my silly exercise. There is a lot still to be said about how this diagram was later used by musicologists in the Qing, in a mode that is empirical rather than speculative, descriptive rather than prescriptive, to analyze phrase structures and period styles. Those uses of this diagram of energetic pulsations that are perhaps closer to the roles played by the Circle in early modern Europe. But that will have to be a different story.

The “featured image” of this post, which Dustin recommended to me, is John Coltrane’s “Tone Circle,” described in depth in a blog by Roel Hollander. If you enjoyed this post and want to learn more about Chinese music theory, check out also Lester Hu’s blog.